Gender and Design: Couple Makers of Design History

Throughout history, there have been multiple ‘power couples’ of designing and making; often husband-and-wife teams, whose overall contributions to the design stage are undoubtedly significant. But how does the recording of their contributions, so often reflective of the times in which they operated, affect the ways in which we view them now? What can we learn from the way that they have been portrayed?

Ray and Charles Eames (Courtesy of Eames Office LLC)

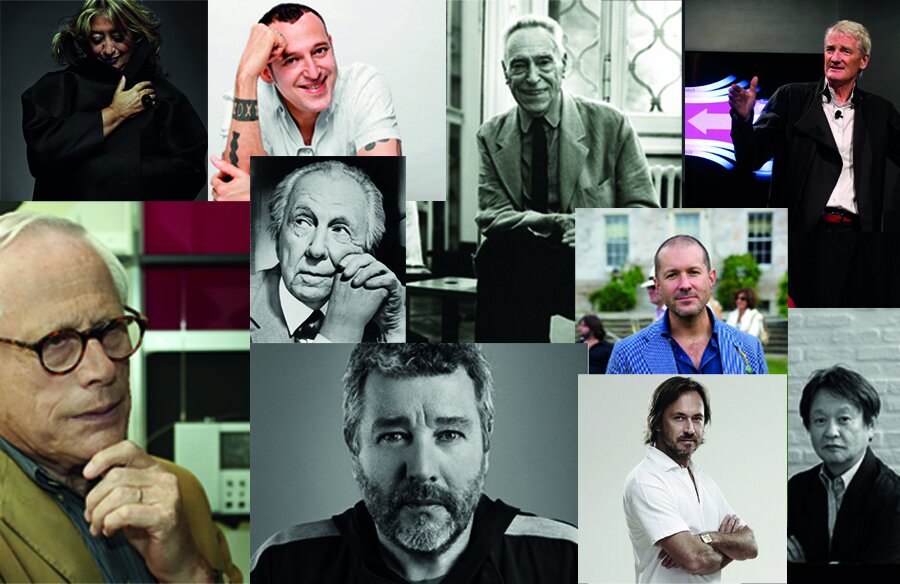

Historically within the Design Community, success has been equated with masculinity. There is an overbearing sense that in order to get anywhere, arrogance, audacity, and self-assertion, traits typically associated with men, are paramount. Within prominent design movements throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, this emphasis on masculinity has inevitably led to the majority of prominent or breakthrough designers being male, with little female representation in acclaimed and influential positions. Take, for example, the following image of the architecture platform ReThinking the Future’s “10 most influential product designers of all time”- featuring just one woman.

ReThinking the Future’s list of the “10 most influential product designers of all time”: Jonathan Ives, Karim Rashid, James Dyson, Frank Lloyd Wright, Achille Castiglioni, Naoto Fukasawa, Dieter Rams, Philippe Starck, Marc Newson and Zaha Hadid (Courtesy of ReThinking the Future)

This has led an approach to recorded design history that has either completely negated the importance and value of women’s design work in relation to their male peers, or created a pedestal for a very small selection of “exceptional women”. The very idea of “exceptional women” designers is quite obviously a problematic concept, as it positions female designers in a competitive position against each other, whilst also creating a narrative that says that there is always a way for women to overcome the patriarchal obstacles that they may face within the design world, if they are talented and work hard. This, in turn, creates a kind of gatepost illusion for female designers, which completely disregards the struggles they have had to face as female designers working within a design culture with roots in the patriarchy. The reality of the matter is that historically, becoming one of the “exceptional women” of design relied more upon the amount that male peers and contemporaries were willing to acknowledge and support women in the industry. This for instance, is exemplified by the work of Denise Scott Brown, and the struggle that she faced in order to achieve recognition for the role she played in the award of the 1991 Pritzker Prize to her husband, Robert Venturi. Despite the Pritzker Prize Jury’s statement asserting that Venturi and Scott Brown’s collaborative body of work had “expanded and redefined the limits of the art of architecture in this century”, the prize was awarded solely to Venturi. The duo both played significant roles in the structuring of the 1960s Postmodern scene, however Venturi, according to Scott Brown, received far more credit and professional acclaim. In “demanding recognition” for her efforts, Scott Brown stated:

“I would be grateful if you would remember that I have worked with Bob since 1960 […] for a very, very long time it has been both of our work, although no one would accept that. ”

Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi (Courtesy of Venturi Scott Brown and Associates)

This patriarchal historical standpoint creates an interesting position when considering the dynamic of Couple Makers, and how they were both received and recorded. The role of the female collaborator has often been dismissed as an assistant or support to their male counterpart, but examining this way becomes far more complex when looking at duo who were not only partners in design work, but also within their personal lives.

Margaret McDonald Mackintosh and Charles Rennie Mackintosh (Courtesy of Glasgow Live)

Take, for example, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret McDonald Mackintosh. McDonald was a renowned artist within her own right, often regarded as an equal by her male peers, and produced many mixed media works in collaboration with her sister Frances, inspired by Celtic imagery. The sisters had their own studio, even created work for William Morris’ Defence of Guenevere. The acknowledgement she received at that point, however, paled in comparison to the acclaim she gained after her marriage to Charles Mackintosh. With him, McDonald became famous for the Gesso panels she created for the interiors that they designed together. Despite this, her work is often historically marginalised in comparison to Charles Mackintosh, who is frequently referred to as “Scotland’s Most Famous Architect”. Much of the work that they created together, such as Glasgow’s famous Willow Tea Rooms, has often been remembered primarily under Charles Mackintosh’s name, despite his reported insistence that “Margaret has genius, I only have talent”. Whilst Margaret is often depicted as an encouraging subsidiary, Mackintosh was vocal about her role in his success, also stating in a letter to her: “Remember, you are half if not three-quarters in all my architectural work…”.

Charles and Ray Eames are another historical example of a couple maker duo in which the male creative, when credited for the duo’s successes, was quick to vocalise the crucial role of his female counterpart. Although widely remembered by media sources as the “wife behind a successful man”, Ray Eames was very much an equal half of a revolutionary and charismatic design duo, who are both credited for their significant contributions and development to architecture and furniture design. Together, the duo created a sizeable collection of collaborative work, some of the more famous examples being the Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman, and the Eames stacking chair for children. They pioneered a range of technologies, including the use of fibreglass in the production of furniture, and in fact, Ray was solely responsible for the design of all Eames fabrics. However, Charles was considered to be the “face” of the duo, despite his consistent advocacy for Ray’s talent: “Anything I can do, Ray can do better”.

Charles and Ray Eames (Courtesy of Eames Office LLC)

Whilst recognised as a part of the duo, Ray never really received all that much credit for her influence upon the design of the 20th century in the same way that Charles did, and her contributions have only recently begun to be perceived in a similar standing as that of her husband’s.

Robert and Sonia Delaunay are a slightly different example of couple makers in that their pioneering work together was not in physical collaborative work, but in the collaborative creation of the abstract, cubism-inspired painting style Orphism. Orphism was a branch of cubism characterised by strong colours and geometric shapes, and although Robert and Sonia produced separate works, they both produced in accordance to the Orphism formula they had co-created. The Delaunays create and interesting example due to the fact that even though they created a movement together, and each produced according to the movement, their process was considered in completely different ways. Design Historian Cheryl Buckley credits this to “socially constructed notions of masculine and feminine”- whilst Robert is credited with having created an entire colour theory, Sonia’s input and influence is portrayed as an “instinctive feeling” for colour and shape. Robert’s work is portrayed as logical, considered, and determined, whereas Sonia’s is reduced to a matter of instinct and emotion- each embodying their respective masculine/feminine stereotypes, no matter the actual influence or equal partnership they may have had.

Robert and Sonia Delaunay (Courtesy of Odessa Review)

“So, what can we learn from these examples of couple makers?”

In order to determine that, we first have to examine the ways in which we view their collective output. In collaborative work, how many times is a female designer credited with adding “humanity” or “emotion” to a male designer’s “intellect” or “logic”? Of course, that is not to say that there is anything wrong with these qualities, on the contrary; it is more the fact that they are societally gendered. In order to view couple makers as exactly what they are, and equal, collaborative partnership, we must first address our own biases. In some ways, couple makers who jointly present their work do some of this for us, however, it is our responsibility as viewers and consumers to ensure our own valuation of the work is based upon an equal accreditation to both halves of the duo, as opposed to minimisation of one party based upon societal prejudices.

Written for Nafisi by Natalie Friesem