Remembering May Morris on her 159th Birthday

May Morris, 1909

At Nafisi, we are in regular conversation about the impact that the Arts and Crafts Movement has had upon our work. Previously, we have discussed the successes and failures of the movement, predominantly focusing on William Morris as the spearhead in promoting the movement as a way of life, rather than just an aesthetic style.

Today, on what would have been her 159th birthday, we wish to champion his daughter, Mary (May) Morris. Although a talented craftsperson and committed socialist within her own right, May Morris’ significant contribution to the Arts and Crafts movement and her personal values as both a creator and a key feminist figure are often overshadowed by her father’s acclaim.

“I’m a remarkable woman- always was, though none of you seemed to think so”

Maids of Honour, May Morris © William Morris Gallery, London Borough of Waltham Forest

As the younger of Morris’ two daughters by Pre-Raphaelite model and muse Jane Morris, May was surrounded by the Arts and Craft designs and principles from a very young age. As well as modelling for her father’s friends, May learnt needlework and embroidery under the tuition of both her mother and her aunt Elizabeth Burden, which eventually led to her enrolment at the National Art Training School. At the age of just 23, May Morris’ proficiency and natural flair for needlecraft resulted in her appointment at Morris, Marshall and Faulkner & co as the department director of embroidery. She is particularly remembered for her role in the resurrection of art needlework, a freehand embroidery technique that, in keeping with much of the Arts and Crafts repertoire, echoed the delicate stitching and shading of Medieval English embroidery. This style was particularly revolutionary due to its emphasis on self-expression for the needleworker; a method that completely contradicted the brightly coloured, ‘paint by numbers’-esque approach to embroidery popular at the time.

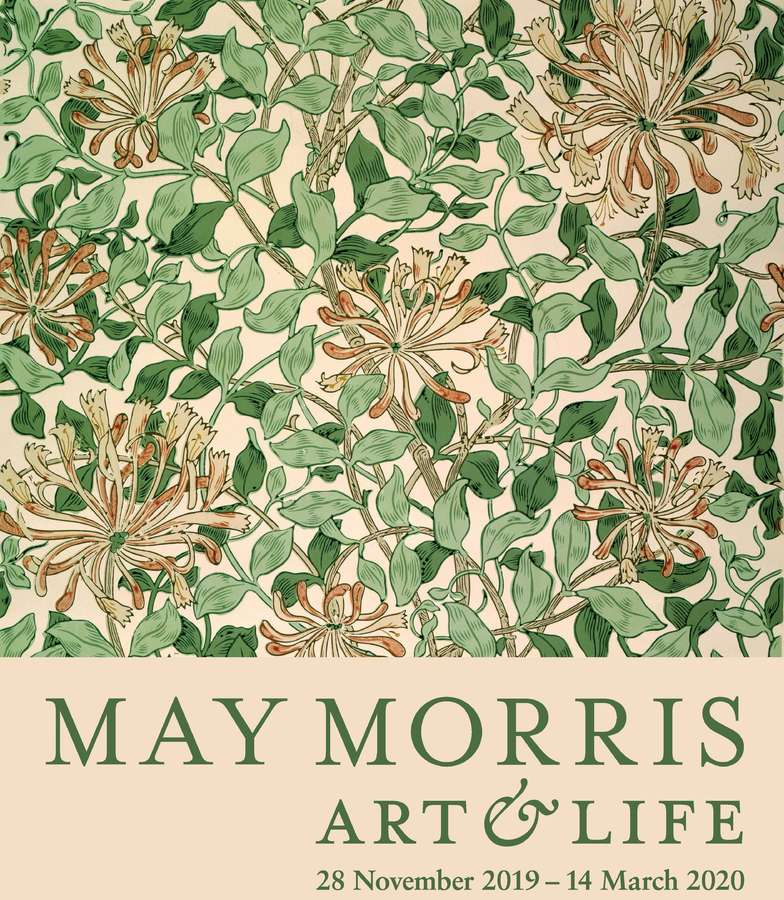

Honeysuckle wallpaper design, May Morris © William Morris Gallery, London Borough of Waltham Forest

Morris, however, was quite the revolutionary in more ways than one. She was particularly active within the inception of The Royal School of Art Needlework, which, under the patronage of Princess Helena, provided women with a pragmatic technical training in needlework. This was a vast difference to the purely theoretical design education courses offered to women in government design schools, and the school grew rapidly, still existing today as the Royal School of Needlework. After leaving Morris, Marshall and Faulkner & co, Morris’ career continued to flourish, freelancing as an embroiderer, designer, teacher, writer and advisor. At the turn of the century, Morris also began to design and make jewellery, some of which is still held within the V&A Museum collection.

Like her father, Morris was also passionately socialist. Initially a part of the Socialist Democratic Federation, both May and William became some of the group’s dissidents, who eventually broke off to found the Socialist League.

“Through her feminist and socialist values, Morris became increasingly frustrated at the lack of recognition and support for female practitioners, which eventually led to her founding the Women’s Guild of Arts in 1907.”

Detail on Maids of Honour, May Morris © William Morris Gallery, London Borough of Waltham Forest

As well as providing a network for female craftspeople, the founding of the guild was a reaction to the patriarchal attitudes of the industry; at the time, membership to the Art Worker’s Guild was restricted to men only, and between 1819 and 1922, there were no female members of the Royal Academy of Arts.

May Morris © William Morris Gallery, London Borough of Waltham Forest

May Morris was an accomplished, passionate, and by all accounts talented designer, so why is her legacy so often forgotten? Ultimately, and unsurprisingly, it is largely down to the fact that Morris was a woman. Admittedly, her creations were predominantly for domestic use, and textile work is notoriously fragile, but the issue remains that her work often fell into the category of ‘women’s craft’ and was therefore denigrated, as was standard practice at the time. Morris’ work never received the public or critical acclaim it deserved, and so, May remained in William’s shadow.

“Recently, as with many other under-appreciated female practitioners of the 19th and 20th centuries, a long-overdue reappraisal is starting to occur, as seen in 2018 at the exhibition: May Morris: Art & Life at the William Morris Gallery in London.”

Through her contributions to the Arts & Crafts movement, extensive body of work, and numerous efforts to uplift other female creators, it is evident that May Morris was, as she asserted, a “remarkable woman”. We believe that to remember her and to talk about her legacy is important in order to treat her as such.

Photograph of May Morris playing a guitar, 1890s - CAGM1991.1016.338 From the Emery Walker Library.